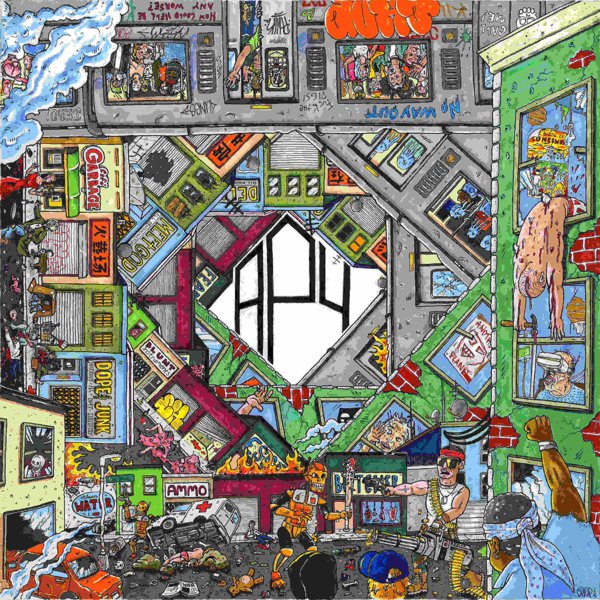

Neighborhood Gods Unlimited

This is the second album cover after Component System with the Auto Reverse that depicts Open Mike Eagle with a ‘90s-vintage shelf stereo receiver mounted over his head — a formative channel of musical experience worn like a protective helmet, a repository of knowledge, and a transmitter all at once. But we’re far beyond merely the second instance of an album where he connects the dots between his trauma, his experience, and his urge to express the relation between the two. At this point, approaching his second full decade of releasing records, he’s honed such a formidable thematic blend of comedy and pathos that he’s joined rare company — the turf of Pharcyde, De La Soul, and DOOM is his to roam. Neighborhood Gods Unlimited feels like a reiteration of his fundamental strengths: his ability to make his perspective feel familiar yet idiosyncratically his own, and the mutability of his quiet-yet-assertive voice, more comfortable with melody than any other lyrical-lyricist rapper has ever really been. Inspired by the concept of a cable network that can only afford to broadcast an hour a week, the album has the impact of a year’s worth of nerves and anxiety condensed into 38 minutes (without commercials), an unspooling of detritus accumulated over a long enough time that it feels kind of exhausting to document it all even at blipvert length. The panopticon can freak him out like the rest of us, transmitting nonstop escalating disillusionment (“i woke up knowing everything (opening theme)”), introducing a thousand little outside assessments into his head (“unlimited skull voices”), and making him feel as though he has to reassemble himself from the busted pieces of his self-conception (“contraband (the plug has bags of me)”, “michigan j. wonder”). But it still stings when he realizes that breaking free of it also means having to lose some of the precious things that helped him channel it, like when he fixates on the existential crisis behind a busted smartphone (“ok but i’m the phone screen”). His trademark dark comedy blunts the bleakness while heightening the absurd; the creative-vs.-day-job double life metaphor at the heart of “my co-worker clark kent’s secret black box” makes the Gunn movie merely the second-best take on the Superman mythos of 2025. And that carries through in heightening the emotional weight when that comedic touch is withdrawn — “a dream of the midnight baby (not a euphemism)” leaves its only real punchline in that title’s parenthetical, its straightforward frankness leaving a vulnerable cast to Mike’s bewildered reaction (“I’m a random in the ghetto/Paying rent, I’m nothing special/I’m not being disrespectful/I just don’t know what to do”). His regular collaborators for beats continue to play to his strengths, with the lo-fi boom-bap hauntology of Child Actor and Kenny Segal’s psychedelic soul sitting comfortably alongside the ethereal headnod beats of first-time collaborator K-Nite. Another welcome (and welcoming) album from an artist at a peak that has not yet become a plateau.