It’s sometimes not fully appreciated – both inside and outside the UK – how many Welsh musicians have been part of the wider tapestry of any number of popular forms in the British Isles from over the post-war decades through to the present day. While there are well known stalwarts such as Tom Jones and Shirley Bassey – both still active at the time of writing in summer of 2025 – numerous other bands and performers have made their mark in ways both high profile and subcultural over time. The famed and tragically fated Badfinger, for instance, began as the Iveys in Swansea in 1961, while Bonnie Tyler, forever known for “Total Eclipse Of The Heart,” was born in nearby Neath ten years prior. Another artist born near Swansea, John Cale, went on to help shape worldwide scenes and styles through the present thanks to both his membership in the Velvet Underground as well as his solo and production work, while Cardiff’s Young Marble Giants, in the space of one album, helped codify a sense of what indie rock was for later generations.

This all only scrapes the surface, ranging from the musician turned all-around entertainer Charlotte Church and heavy metal veterans Bullet For My Valentine to the protometal stalwarts Budgie and the 1950s revivalist Shakin’ Stevens, from the post-punk sweep of the Alarm and Gene Loves Jezebel to the sturdy – some might say stodgy – work of the Stereophonics and Catfish and the Bottlemen, not to mention the comedy rap doings of Goldie Lookin Chain. The newer work of acts like sisters and Pipettes veterans Gwenno and Ani Glass, both of whom record in Welsh and Cornish, as well as Race Horses’s Dylan Hughes doing solo work as Ynys and the unsettled experimental folk of Tristwch Y Fenywod, not to mention the wider efforts of labels like Recordiau Prin, are among the many reasons Welsh music thrives.

With this in mind, and noting out of the gate that this overview is hardly going to be definitive by any measure, there’s something to be said for the particular ferment of Welsh acts in a generally indie/alternative rock style that attracted attention in the 1990s for their work. Whether being notably experimental, engagingly poppy or aiming for the arena heights – or all three and more – there’s little doubt that a lot was going on at the time. If sometimes collectively described and perhaps stereotyped as a response to the overweening impact of ‘Cool Britannia’ as such by the mid-1990s – the phrase ‘Cool Cymru,’ referring to the Welsh name for the country, is sometimes used – the sense remains that most of these acts, many with shared roots or growing out of earlier incarnations of other acts, absolutely had something distinct happening.

Some musicians had associations with what were already long established circuits for Welsh language music in particular, most often associated with real or perceived purist folk roots, via a network of labels like Sain, founded in 1969, as well as the Welsh language broadcasters Radio Cymru and later the TV channel S4C. But ever since the pioneering late 60s work of Meic Stevens in particular, Welsh language releases had somewhat fitfully grown into its own collective engagement with wider pop trends. This essay is not a place to fully and firmly unpack that history or associated questions of language, Welsh nationalism, identity and the decision to record in English or not, but five years after the Anhrefn label, founded by the legendary punk act of that name, began supporting newer acts steering clear of traditionalist cul-de-sacs, a flashpoint was reached with the start of an essential imprint in 1988. The brilliantly named Ankst was dedicated to more cutting edge sounds in what was termed Y Sin Tanddaerol – literally, ‘the alternative scene’ – and whose own relation to the Welsh language establishment as such can be summed up by a Beck-referencing compilation title: S4C Makes Me Wanna Smoke Crack.

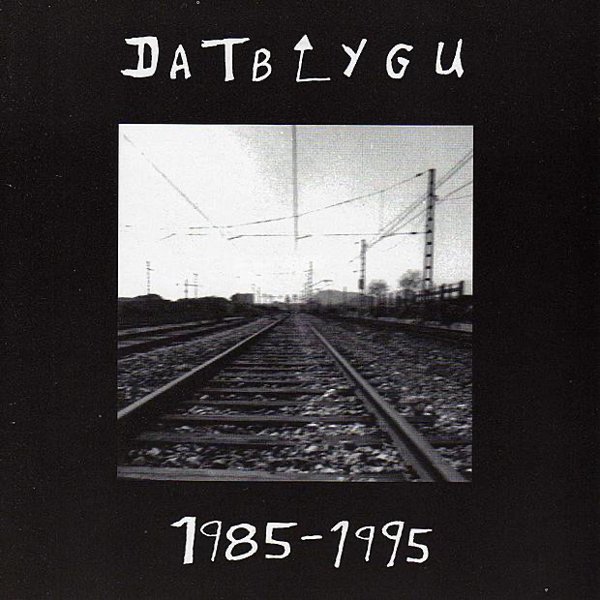

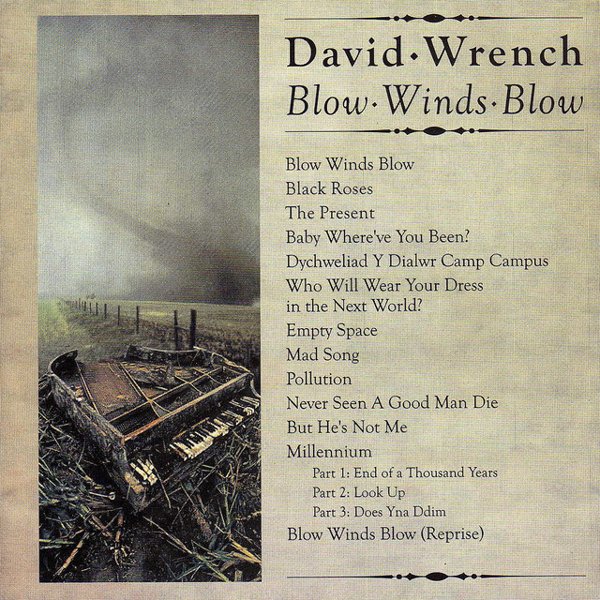

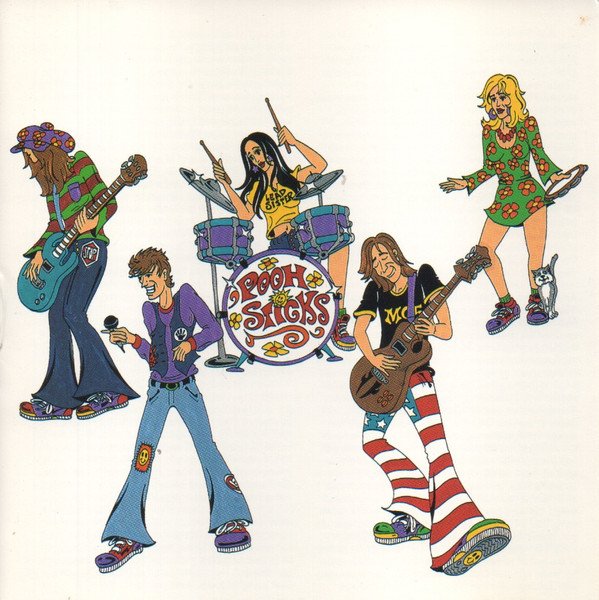

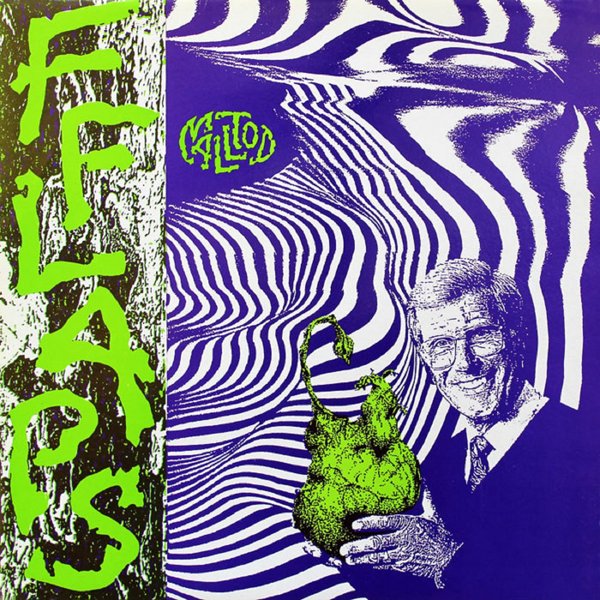

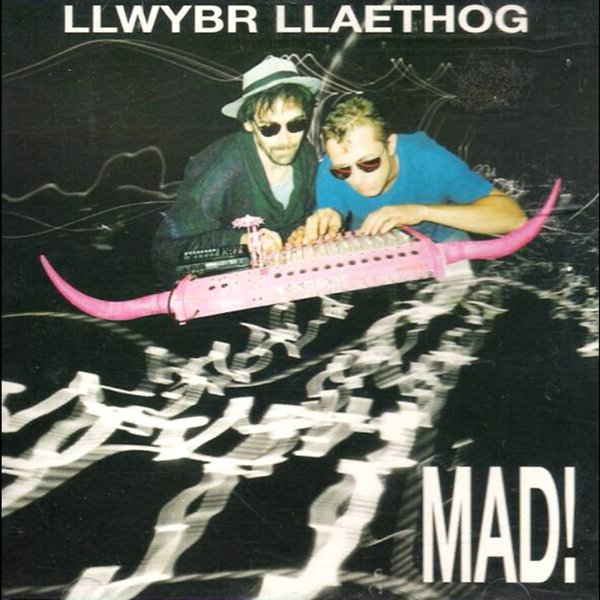

The acts listed here, drawing on releases from or compilations focused on the 1990s, are not all Ankst veterans by any means; certainly not all were singing in Welsh even from the start. Sain’s sublabel Crai, also founded in 1988, had its own part to play among other imprints, while a key musician and production and engineering figure, Gorwel Owen, had been working with many bands across any number of labels since the early 1980s. Some groups, like the Darling Buds and the Pooh Sticks, emerged first in the mid- to late-80s as part of the wider C86 scene. The genre mixing Llwybr Llaethog started around the same time, while Datblygu were already underground legends dating back to 1982. Other groups were partial continuations of earlier identities, with Fflaps transforming into the majestic Ectogram, while members of Y Cryff and Ffa Coffi Pawb switched from their previous Welsh-centered approaches to make notable English language impacts with their new acts: Catatonia and Super Furry Animals, respectively. Then there’s the astoundingly madcap prog/psych world of early Gorky’s Zygotic Mynci, a universe of its own, while the brilliant indie-pop legends Helen Love, though they only released their first full debut album in 2000, spent most of the 1990s putting out a series of regularly compiled singles and EPs.

Yet unquestionably the band that turned into true superstars in the UK and beyond pursued their own burning path almost from the get-go when they initially formed at school in Blackwood in 1986. Manic Street Preachers had one of the 1990s’ most erratic and surprising stories, from their aggro glam-punk ‘take on anything and everybody’ start, which signing to a major label didn’t change in the slightest, to the fraught, harrowing power of one of the decade’s strongest rock albums anywhere, The Holy Bible, to the tragic disappearance of key lyricist Richey Edwards and the subsequent Britpop landmark full length smash hit Everything Must Go, which put them in a mainstream firmament they’ve never quite left. Even now they’re planning a sixteenth album – and while they were at it, contributing a song to a 2009 Shirley Bassey album.