“Chamber jazz” is one of the more amorphous musical descriptions around. It’s a little better than the somewhat related “Third Stream,” which tells you exactly nothing unless you know what streams 1 and 2 are (jazz and classical), but it’s still hard to read the phrase and immediately hear a sound begin to take form in your head the way you can with “soul jazz” or “free jazz” or “smooth jazz.”

To put it simply, chamber jazz is jazz with the qualities of chamber music. The pieces are more thoroughly composed, rather than being melodic heads used as a springboard for improvisation. The instrumentation tends to be quieter and more subtle. There may be strings (but not an orchestra), and there may not be drums. Despite these factors, though, chamber jazz — at least in the 1940s and 1950s, when the style first began to develop — retained a swinging rhythm and kept at least one foot in the blues.

The emphasis on composition and a certain genteel attitude are what sets chamber jazz apart from other styles, but it’s not something anyone specializes in. The description is applied from without, by critics and scholars. Still, it’s possible to point to certain early works, like Duke Ellington’s “Reminiscing In Tempo” (a tribute to his mother, recorded in 1935 and spread across four 78 RPM sides) as setting out a path for others to follow. Clarinetist and big band leader Benny Goodman’s small group recordings of the mid ’30s were also key early examples of chamber jazz: the original trio featured Teddy Wilson on piano and Gene Krupa on drums, later joined by vibraphonist Lionel Hampton.

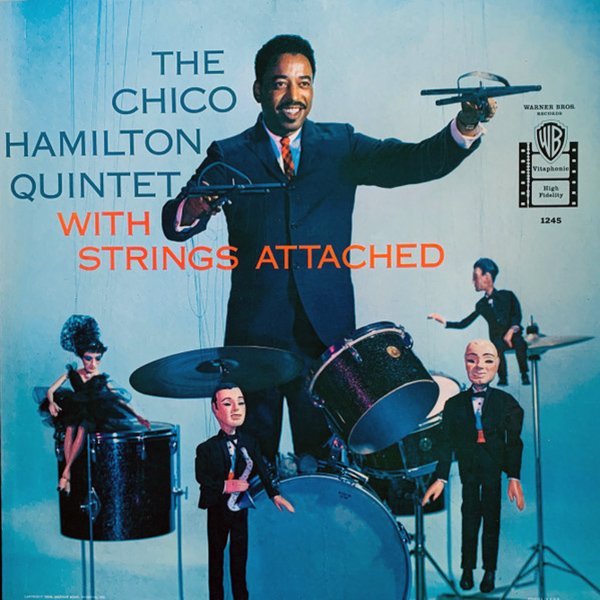

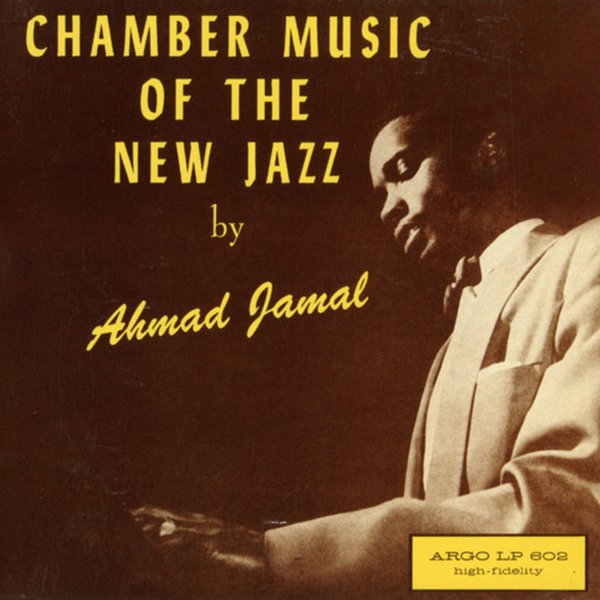

In the 1950s, artists like pianist Ahmad Jamal, drummer Chico Hamilton, and the Modern Jazz Quartet refined chamber jazz into something close to a defined style. The MJQ in particular explicitly presented theirs as concert music; pianist John Lewis’s compositions were elegant and restrained, drawing inspiration from baroque music.

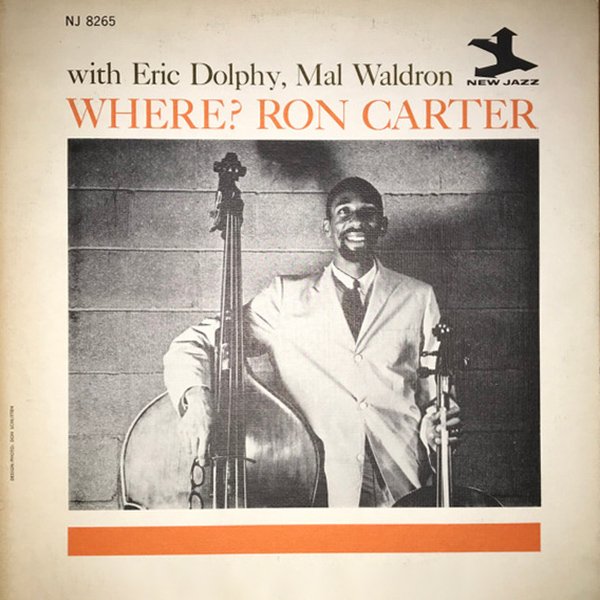

Chamber jazz doesn’t have to be a reactionary form, though. There’s plenty of room for avant-garde experimentation, as artists like clarinetist Jimmy Giuffre, bassist (and cellist) Ron Carter, and others proved in the 1960s. Carter’s Where? featured Eric Dolphy on various reeds and Mal Waldron on piano, while Giuffre’s trio with pianist Paul Bley and bassist Steve Swallow played a hushed, meditative version of free jazz with none of the bluster typically associated with that style. Similarly, trumpeter Bill Dixon’s Intents And Purposes, from 1967, combined a piece arranged for a 10-member ensemble with solo music, a trumpet-flute duo, and a quintet piece, all of a uniquely atmospheric character.

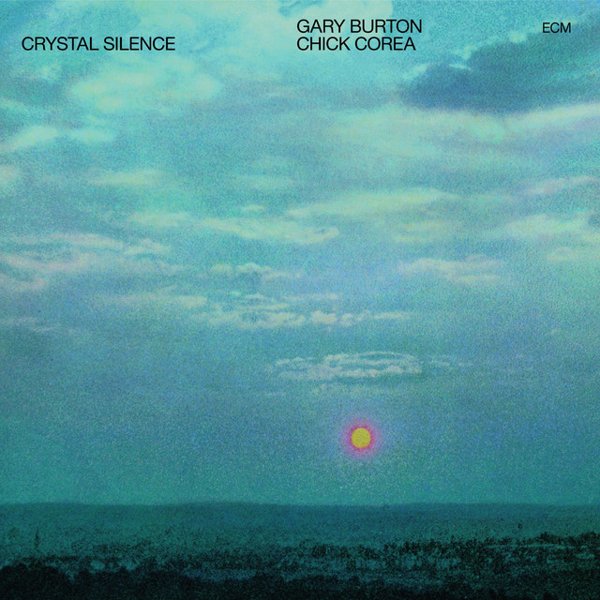

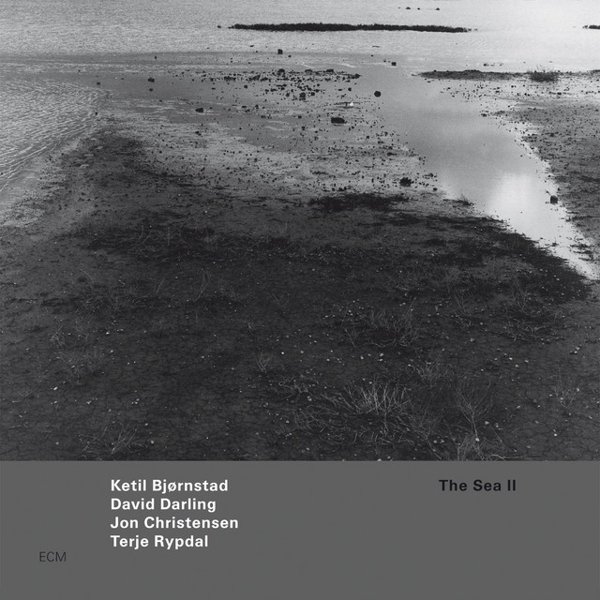

For many listeners, chamber jazz is identified with the Nordic and other European musicians signed to the ECM label; their pastel soundscapes have the beautifully crafted sound and general restraint of classical recordings, even when the music is challenging. Bassist Eberhard Weber’s The Colours Of Chlöe and the piano/vibes duos of Chick Corea and Gary Burton, as well as guitarist Ralph Towner’s Solstice, are paradigmatic examples of chamber jazz and “the ECM sound,” two things that aren’t really a thing, but can sure seem like it.

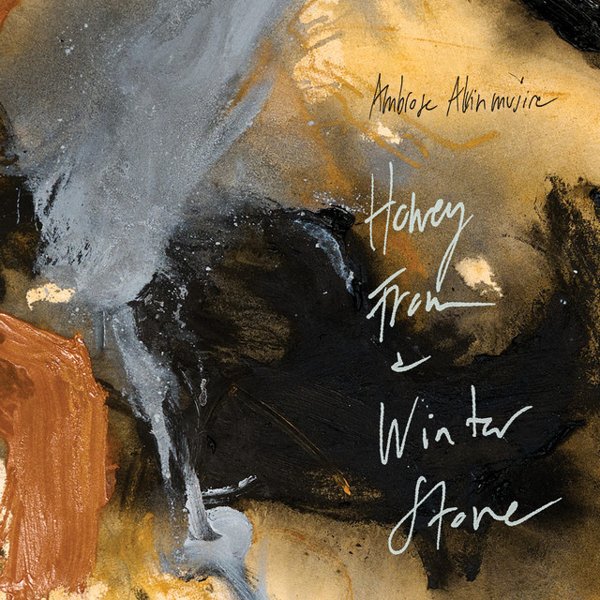

Even musicians identified with louder, more aggressive music have some chamber jazz in them at times. Cecil Taylor’s 1978 Unit made some of the most tightly arranged and classically romantic music of the pianist’s career, and Matthew Shipp’s String Trio with viola player Mat Maneri and bassist William Parker has recorded several albums of gemlike miniatures. In recent years, players on jazz’s cutting edge like guitarist Mary Halvorson and trumpeter Ambrose Akinmusire have let their composer’s side emerge on records with strings, vibes, and other chamber jazz instruments up front, showing that the sound isn’t going anywhere anytime soon.

Perhaps the key to understanding chamber jazz is less as a genre than as a field for exploration, open to any musician who wants to bring the intensity down for a while and let their music breathe, while still retaining the compositional rigor that great art requires.