Both of the two recent films about gifted, troubled orchestral conductors have scenes where the protagonist conducts music by Austrian conductor and composer Gustav Mahler (1860-1911). In Todd Field’s Tár (2022), main character Lydia Tár is shown flashing various aspects of her genius during a rehearsal of Mahler’s Fifth Symphony, demonstrating a super-power-like competence that the film ultimately exposes as a mask for toxic, controlling behavior. A scene of Leonard Bernstein in the throes of conducting Mahler’s Second Symphony in Maestro (2023), serves a similar purpose. Bernstein’s thrilling and self-immolating performance is a foil to the film’s prevailing focus on his self-absorption and its effect on his relationships. In both scenes, the performances are temporary triumphs, suspensions of the laws of human gravity, an illustration of what flawed people can accomplish in certain transfixing moments.

It is not surprising that these contemporary looks at the culture of Western classical music hover over Mahler’s work. At one level, performing Mahler is still considered the ne plus ultra of orchestral conducting; someone who can effectively shape the tangled literary and philosophical discourses, dense networks of musical ideas, large performing forces, and mammoth lengths can seem preternatural. But at a deeper level, both Mahler’s work and performances of it point right to a central tension in the history Western art-music tradition — the contradiction between the spell-binding achievements of great figures and their complexities as individuals. Bernstein and Tár are complicated conductor-figures who flash omnipotence, and before them, there was Mahler, one of the archetypes of the complicated, brilliant modern conductor.

Mahler’s output (primarily 10 symphonies, mostly with voices and/or choir, and a number of song cycles) can seem unapproachable, weighed down by its huge dimensions and the plethora of ideas within and without it. But it is at its most intelligible when it is confronted straightforwardly; it is, at the end of the day, just music. One example of how interpretive traditions can obscure the simple, open hearing of it is the beginning of the Ninth Symphony. Many program notes will tell you that the rhythms of the opening minutes of the piece refer to the heart condition with which Mahler had been diagnosed in 1907. This is Bernstein’s suggestion, and it is an interesting one. But purely musically, it is an arrestingly mysterious piece of writing, as hushed fragments passed between corners of the orchestra give way to a two-note, sighing figure that is beautifully and inexplicably sad. Despite the amount of ink spilled by Mahler and others about the meanings of his music, it is important to not forget that he was ultimately a working musician, a great orchestrator, someone capable of composing striking and ambiguous musical ideas that invite interpretation without providing easy answers.

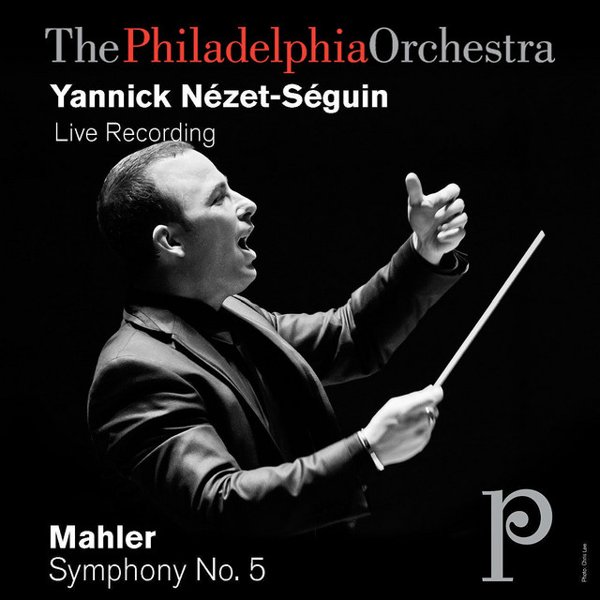

Mahler’s orchestrational skill, undoubtedly a product of his demanding conducting schedule, is consistently one of the most amazing features of his music — the opening of the Fifth Symphony depicted in Tár, for instance, where a single trumpet solo suddenly gives way to a giant, full-orchestra march. Turbulent seas of melody can create an awe-inspiring sense of multiplicity: see the opening of the Eighth Symphony, or of Das Lied von der Erde; at other points, spirals of melody are frightening and claustrophobic. And while it is most famous for panoramic orchestral vistas (see the scene in Maestro), it can also be understated and tender, like the pianissimo opening of the Ninth, the first of the Kindertotenlieder, or the famous Adagietto movement from the Fifth Symphony, a memorable part of Visconti’s Death in Venice.

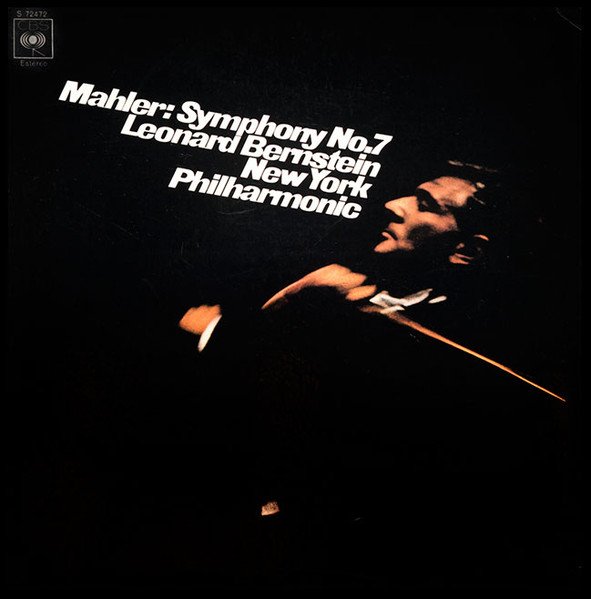

Mahler’s influence on twentieth-century culture is surprisingly manifold. Maestro gestures toward Bernstein’s obsession with Mahler, a cultural legacy of the 1960’s that propelled Mahler once and for all into the canon. Though he has long been a mainstream staple of the repertoire, he was also a formative influence on the twentieth-century avant-garde: Schoenberg, Berg, and Webern, tone-setters for important strands of modernism, all revered him. He was also a significant influence on the modern classical concert ritual — no clapping between movements, no showing up late. This points directly back to his approach to the symphony and to music — a reverential space wherein the truths of human experience are traced through sound. Mahler shouldered everything in his music – the full weight of tradition, the responsibility of public art, and the deepest existential questions, which for him seem to have remained remarkably acute until the end of his life. The best recordings of his synthesize these complex undercurrents with genuine and straightforward musical excitement.