“The south got something to say,” said Outkast’s Andre 3000 on the cusp of fame at the 1995 Source Awards. He was talking about the hip-hop world’s condescending dismissal of most rap scenes outside of the coasts. Independent record labels documenting and furthering local scenes and owned by an artist, someone adjacent to the artist or otherwise outside of the white music industry establishment were pervasive in hip-hop by then and were popping up everywhere – LA’s Death Row, New York’s Bad Boy, Atlanta’s So So Def, Houston’s Rap-A-Lot. At the time of the 1995 Source Awards, No Limit Records had just relocated from Oakland to founder Percy “Master P” Miller’s hometown of New Orleans, and they were so off the radar that it seemed unlikely they would play a crucial role in permanently making the South the center of rap music.

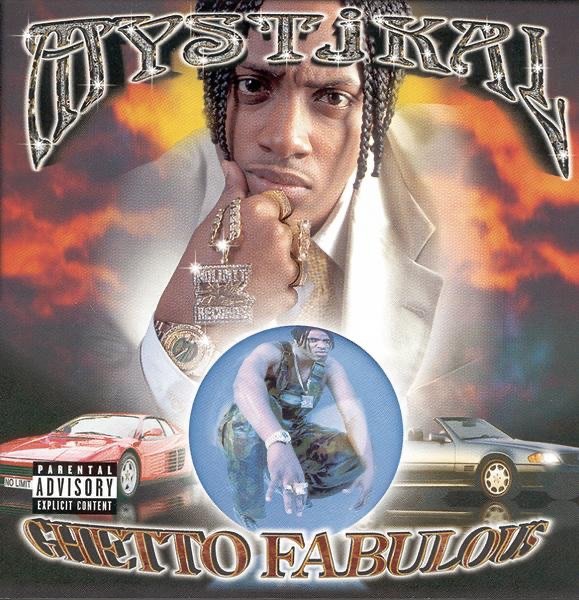

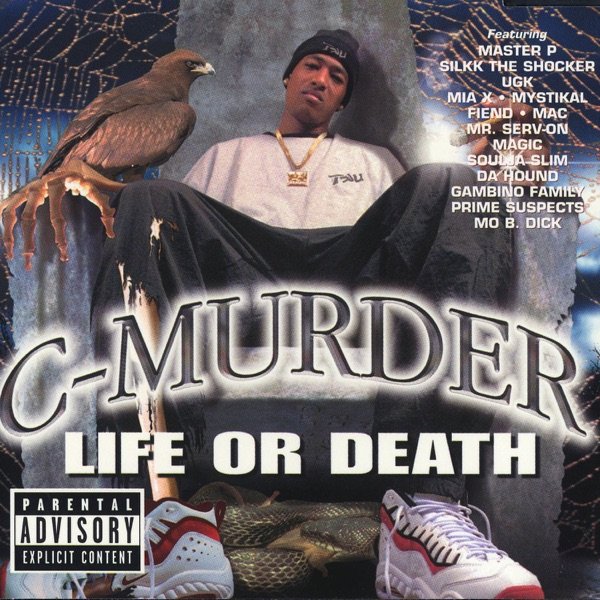

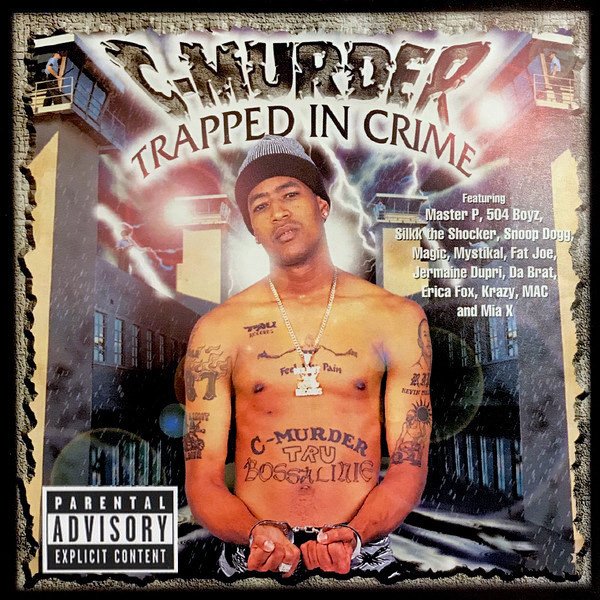

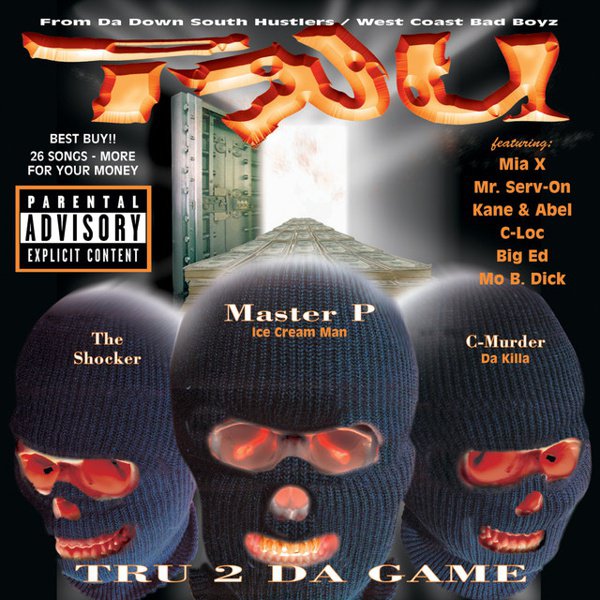

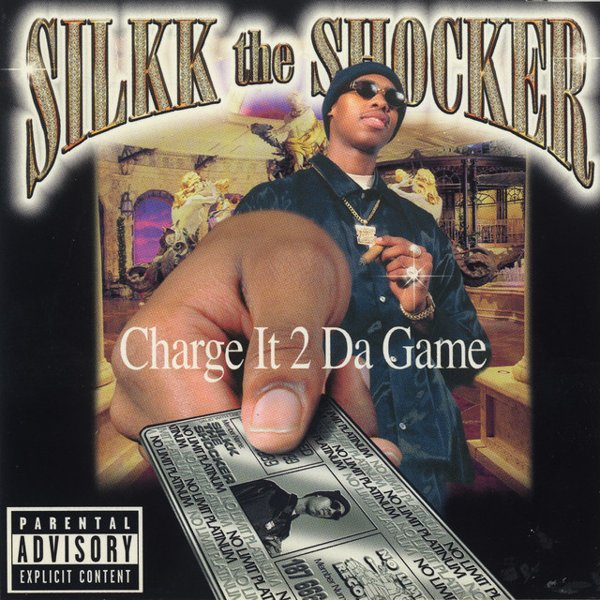

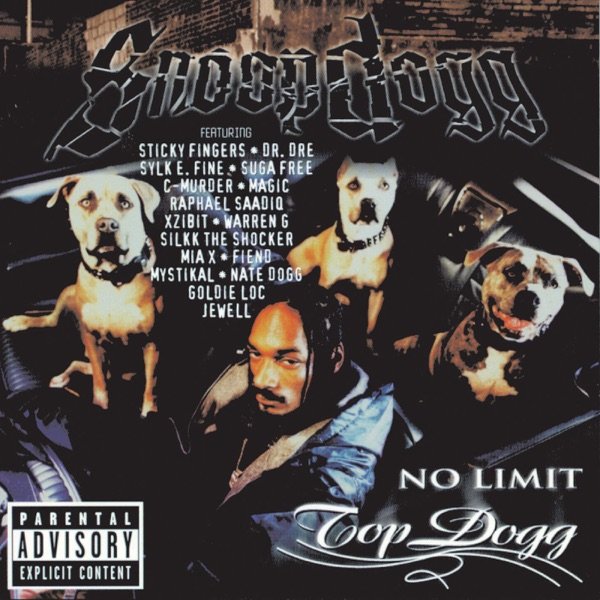

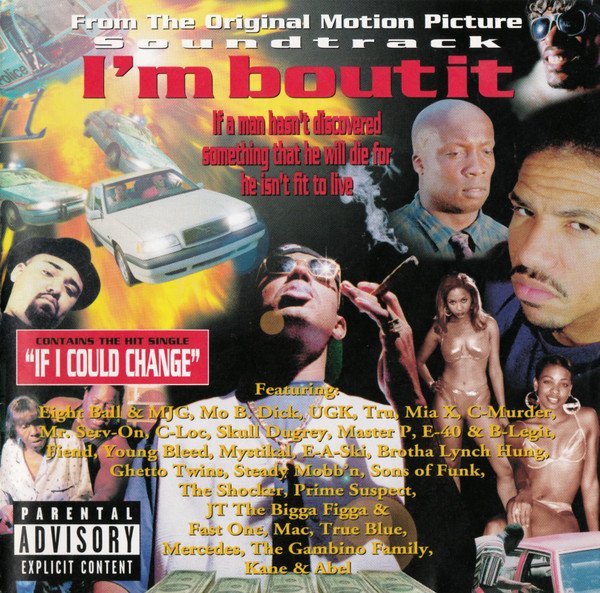

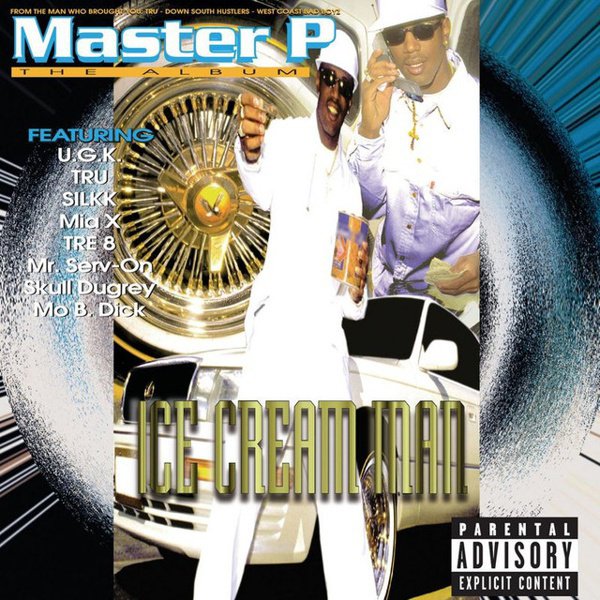

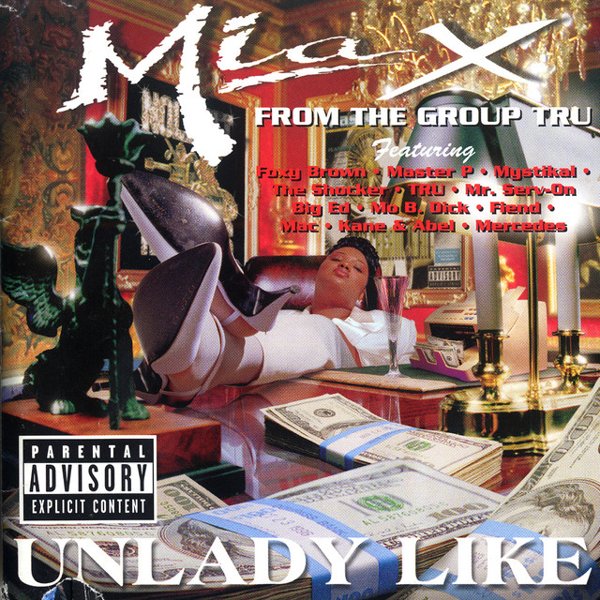

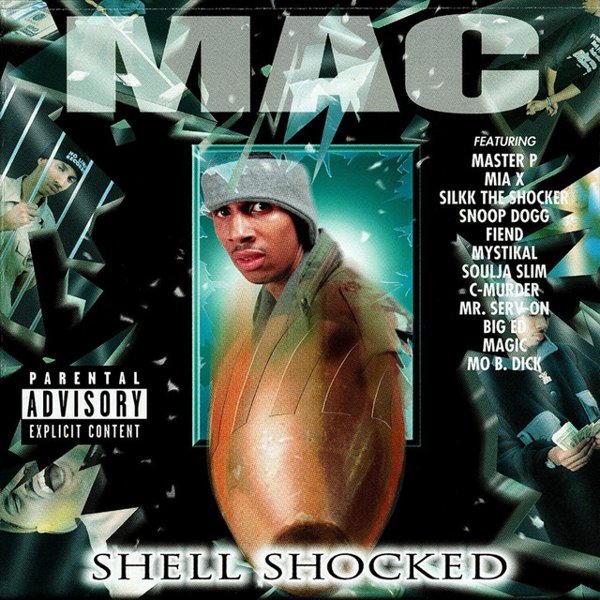

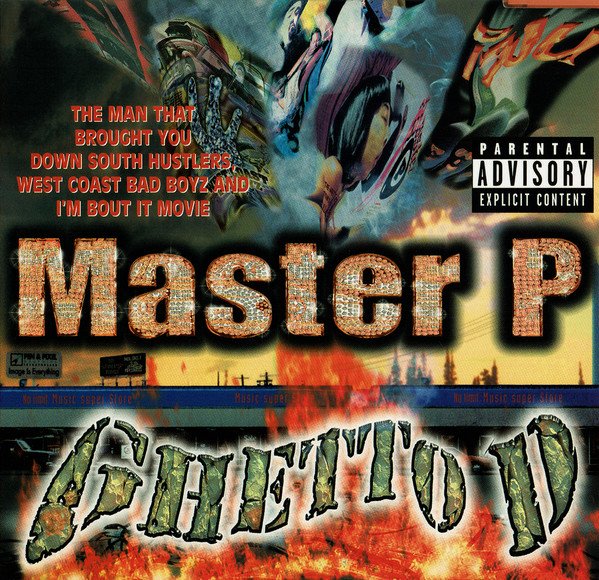

But they built up a regional audience, and No Limit’s breakout release was Master P’s 1996 album Ice Cream Man. It entered the Billboard Top 10 and began a remarkable four-year streak of popular No Limit releases. Master P’s innovation was to bring market saturation to gangsta rap – dozens of albums were released in each of the last years of the 1990s, always advertised by brightly colored inserts included in everything issued by the label. Sometimes, music was included in the advertising before a note had been recorded. These strategies created the impression of a large, unified scene, especially with the instantly recognizable bounce of tracks by production team Beats By The Pound on almost every song and the Pen & Pixel art on every cover. The label’s main artists were Master P and his brothers, C-Murder and Silkk The Shocker. They appeared in endless configurations of solo and group recordings with other New Orleans artists such as Mia X, Kane & Abel, Mr. Serv-on, Mac, Young Bleed and Mystikal, working in lockstep as the self-styled No Limit Soldiers.

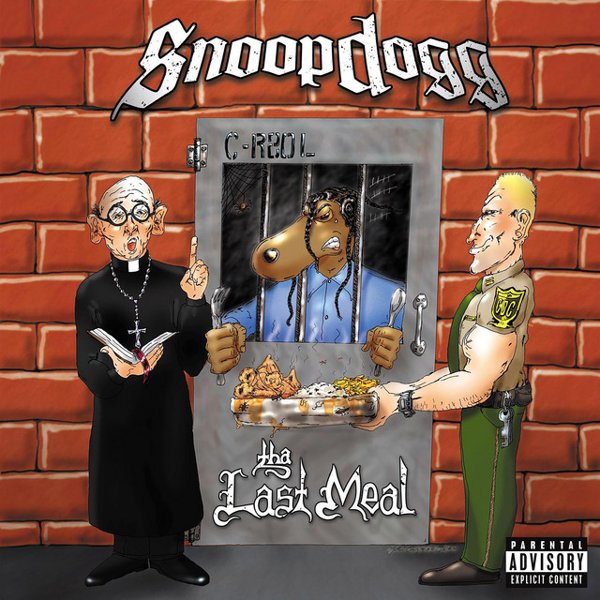

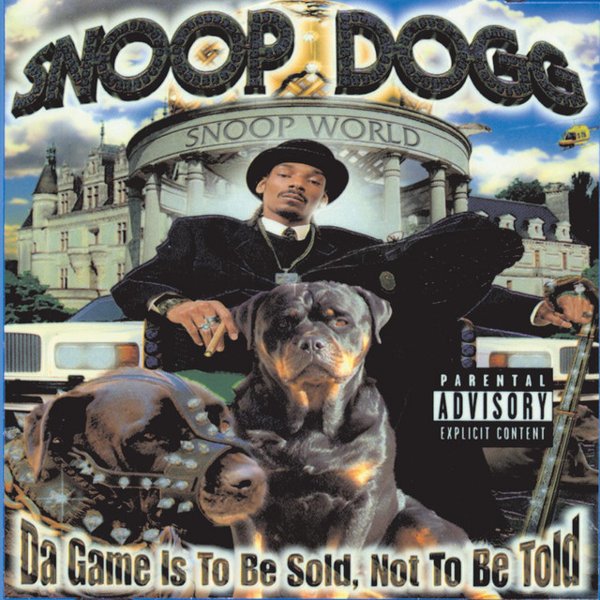

For a while, it worked better than anyone might have expected. The label cultivated an immense and loyal following in the South and then nationwide. Album after album went gold and platinum. The first No Limit film, I’m Bout It, hit theaters in 1997. There was No Limit clothing, No Limit phone sex lines, even a No Limit real estate agency. Some critics claimed that the music bordered on self-parody, but that did nothing to stop the label’s ascendancy, finally peaking in 1998. There was a real pop hit that year, “Make ‘Em Say Ugh” by Master P, Silkk, Mia X and Fiend. Master P also signed Snoop Dogg the same year, on his way out from Death Row, which lent No Limit considerable credibility. They were no longer a ragtag collection of unsophisticated southerners, and Snoop’s label debut found many critics making their peace with the label. Ten of the company’s releases were certified platinum in 1998, a shockingly high number for an independent label.

After that high point, it was steadily downhill until No Limit finally sputtered out around 2001, amidst allegations of sketchy business practices. Boilerplate gangsta music simply became less popular as the decade closed out. It’s impossible to overstate how overexposed No Limit and its artists were at the time, and the public moved on.

No Limit was a collection of rap’s most gaudy cliches. Monosyllabic gangland tales that were the straight-to-video alternative to Biggie and Wu-Tang’s Scorsese verses. Chintzy, photocopied versions of G-funk tracks that sounded like they were presets on budget keyboards. Most infamous were the album art and promotional materials by Pen & Pixel – shiny, hallucinogenic collages of gleaming diamonds, mansions, pit bulls, half-naked models, and cash in a garish dimension where the party never ends.

But time has been extremely kind to No Limit. Much of the label’s pre-1997 music has a thudding homespun charm. From ‘97 on, the best releases were exciting and inventive. Producers Beats By The Pound tempered Californian G-Funk with a deep southern bounce that looked back to New Orleans jazz and ahead to trap. The repetitive chanted lyrics were hypnotic and cathartic, riding a thick, messy foundation of ricocheting beats. Master P’s shameless money-chasing business practices have been normalized in rap, rock, and pop, and every social media influencer apes his ideas, although “diverse income streams” is the euphemism. That gaudy, tasteless Pen & Pixel artwork style has become a mainstay in music and fashion design, and you can buy versions of it at any flea market in the world. Was Master P a cultural visionary? By any metric, he absolutely was.