Sometimes it’s possible to make a guide that’s very comprehensive – say, if you’re talking about a very local scene in a specific couple of years. Sometimes a guide can be semi-comprehensive, giving at least an overview of a particular sound or historical strand. But this… this guide is the opposite of comprehensive. That is to say, its subject matter is impossibly huge, and impossibly loosely defined, so the purpose here is not to explain or to contain but to point outwards in many directions, offer a few starting points, and say “off you go” as you begin your own explorations.

At the time of writing, in 2025, “Afro-house” has become kind of codified as a very commercial strand of the global dance music economy. It means something smooth and lightly funky, full of signifiers of sunshine and exoticism, for wealthy audiences to luxuriate in. DJs from South Africa play undemanding sets on Russian oligarchs’ yachts moored off Ibiza for $500k a time and it’s all very decadent. But in fact, the relationship of house music to the African continent and its cultures is… well it’s as old as house music itself and older, and has been explicitly explored in many different forms over the years.

From the outset, house obviously contained rhythms and structures that had come down both through African-American music traditions of jazz, blues, funk, disco and co, and through the Afro-Latin and Afro-Caribbean styles which were woven into them, taking these influences into the new technologically-assisted era. This came to the fore now and again through the early days, whether through sampling of Afro-disco classic “Soul Makossa” by Cameroonian genius Manu Dibango, the huge acid house era remixes of Guinean singer Mory Kante’s “Yeke Yeke,” or looping of unidentified “tribal” chanting in underground classics like No Smoke’s “Koro Koro.”

As house became a global force and ever more complex and sophisticated as a form, people within its establishment became more conscious of these connections. Artists like Joaquin “Joe” Clausell, Osunlade and Masters At Work began exploring their African-American, Afro-Latin and ultimately African heritage. Paris had long been a centre for recording artists from the former French colonies, and much of their music had entered the French vernacular so it became very natural as house became dominant in France for producers like Frederic Galliano, Bob Sinclair and DJ Gregory to not only sample but work with vocalists from Mali, Senegal, Côte d’Ivoire among others. In Britain a tight knit but passionate broken beat scene added the rolling rhythms of Fela Kuti-style Afrobeat as a key ingredient in its piquant brew of soundsystem bass, jazz, funk and techno, all at a house tempo.

But this wasn’t a one-way street. Far from it. The history of African diasporic music has always been one of criss-crossing influence, of call-and-response – as, for example, when Cuban salsa records reached West Africa and created whole new musical forms like highlife, which in turn reverberated across the entire continent. So house, along with hip hop, reggae and other modern styles, quickly took root in different African countries, house itself most notably in South Africa where it became a culturally dominant form, sprouting local variants, most notably the slow, rugged kwaito.

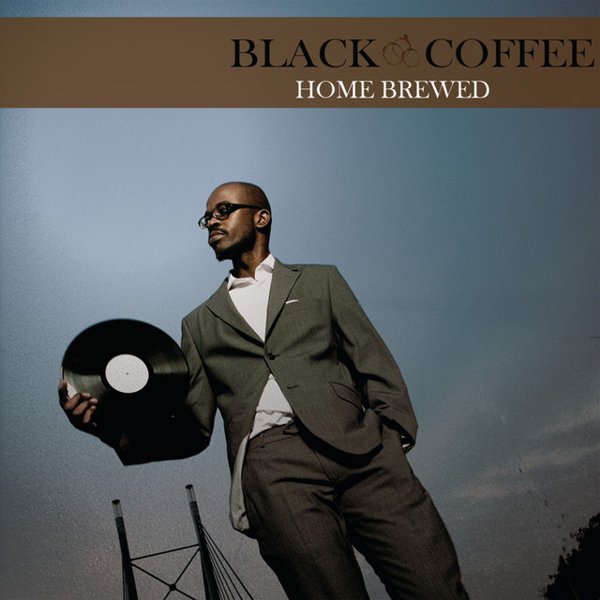

But house AS HOUSE also remained huge in S.A. too. Not just any old lowest-common-denominator globalised house, but the funkiest, most sophisticated, most musical house – that which was most in touch with its own African roots, in fact, whether that be Masters At Work, Bang The Party or Kerri Chandler. Stories abound of producers in the UK, France, Belgium and the US who were considered niche at home discovering their tracks were blowing up and selling by the thousands, thanks to grey-economy mix tapes and CDs sold by taxi drivers in S.A. South Africans also learned to master these tempos and patterns too, eventually in the 00s launching one off international hits like DJ Mujava’s “Township Funk” and then whole careers for DJ/producers like Black Coffee.

House – and techno – also reached into the neighbouring former Portuguese colonies of Angola and Mozambique, too, but were quickly absorbed into entirely new styles like the hyperactive kuduro and tarraxinha, which were once again in transatlantic dialogue, this time with the electronic funk sounds of also Portuguese-speaking Brazil. As the 21st century began, things started to get more complex still as the African heritage population around Lisbon began to pick these sounds up, creating their own strange and heavy batida sound. Likewise African house was increasingly picked up by young Black British DJs and producers, fusing with American house, grime and broken beat to make the unique party sound of UK funky.

All of these different strands generated vast quantities of music, but that was as nothing to when South Africa’s love of house matured and created whole new offspring: first the dark, disquieting, starkly electronic sound of gqom, and then the elegant, gliding – but still dramatic – groove of amapiano. Amapiano flipped typical dance music structure and the fast-cut overstimulation of the EDM age on its head, letting everything be about steady progression rather than waiting for a big “drop” again and again, tantric in its prolongation of pleasure. It was the sort of dramatic shift in dance music dynamics that everyone thought didn’t happen any more, and it became an instant global sensation in the early days of Covid as millions trapped at home tuned into streams of South African DJs playing in idyllic poolside or balcony settings.

Amapiano particularly exploded in Nigeria, already the home of many global superstars, and from there reached a huge diaspora as a party sound. Since then it, along with the more generalised “Afro house,” has been adopted by musicians from Beyoncé and Drake on down, as well as sparking enduring scenes from Saigon to Santiago and adding a whole new strand to the UK raving scene alongside the old multicultural staples of jungle, garage, grime, dubstep and funky, and of course they’ve both also morphed into a deluxe version for penthouses in Dubai and those superyachts looming in the background in Ibiza. But which part of this is the definitive Afro house? Well that’s the point… you cannot define it, any more than you might define “African music.” But what you can do is realise there is a deep and rich history and dizzying present of continuing conversations and cross-fertilisations, full of untold weird and very wonderful variants, and start digging in. So herewith a few starting points… off you go!