It’s been a long journey for Chicago House, from its origins in the black, queer underground dance clubs of Chicago to its current cultural ubiquity, but it’s a journey that can be neatly and accurately summed up, to quote house music Godfather Frankie Knuckles’ famous phrase, as the story of disco’s revenge.

By the late seventies disco was selling millions worldwide, but the market became oversaturated as record labels scrambled to earn as many disco dollars as they could before the glitterball bubble burst, releasing beige disco takes from risible old rockers like The Kinks and Rod Stewart. As the sound became ever more watered down for mainstream taste, disco’s musical innovations descended into predictability and caricature, provoking a backlash: it was too rigid or too synthetic, too commercial, too camp, or somehow threatened rock music values, whatever they might be. And for some, these criticisms tied into prejudice towards blackness and queerness, with hatred of disco becoming a handy veneer for racism and homophobia.

In July 1979, Chicago radio personality/shock jock Steve Dahl put on a radio promotion event called Disco Demolition Night at the Chicago White Sox ballpark. Admission to the evening’s game was lowered to 98 cents (the radio station being promoted was WLUP 97.9 FM) for anyone who bought a disco record with them, which were then piled up in the centre of the park and blown up. A riot ensued, there were thirty-nine arrests, and Dahl’s national popularity got a bump. Chicago house music innovator Vince Lawrence was there that evening and recalled that people weren’t just bringing disco records, they were bringing anything with a black face on the cover. He found himself in an ugly melding of prejudices as a rioting crowd of white men destroyed black music, music supported by a core queer audience, sung largely by women.

The event signalled a turning point for disco nationally and labels shut their disco departments, R’n’B tempos slowed, radio stations switched back to rock, and the Grammys cancelled the Best Disco Recording category. But as seminal Detroit producer Juan Atkins told author Simon Reynolds in Energy Flash, “Chicago was one of a couple of cities in America where disco never died. The DJs kept playing it on the radio and the clubs. And since there were no new disco records coming through they were looking to fill the gap with whatever they could find.”

This was the context in which Chicago house music was created. The place was The Warehouse club on 206 North Jefferson, Chicago, the time was Saturday night to Sunday afternoon in the late 70s and early 80s, and the instigator was resident DJ Frankie Knuckles. The first house record released on vinyl was in 1984, but the first time Knuckles heard the term was in ’81, when, driving through Chicago, he saw a sign in a bar window that read WE PLAY HOUSE MUSIC. Asking his friend what it meant he was informed, “It means music like you play at the Warehouse.” At the time Knuckles was playing the post-disco of labels like Prelude, TK Disco and West End, and to counter the lack of new up-tempo four-to-the-floor dance records, he added Italo disco, Euro-synth, weird dubby imports or rock obscurities with a decent drum beat to his DJ sets. Knuckles had also bought a new style of DJing with him from New York’s gay disco and bathhouse scene when he’d relocated to Chicago in 1977, using a reel-to-reel tape recorder and drum machines to re-edit and re-work old disco records, extending vamps, breakdowns and instrumental sections, adding sound effects and new drum beats, giving popular but over-familiar songs a brand new lease on life.

Knuckles left The Warehouse in ’82 to start his own Power Plant venue, The Warehouse was renamed the Music Box and legendary Chicago DJ Ron Hardy — “the greatest DJ who ever lived,” according to Chicago House legend Marshall Jefferson — was installed as resident. The two DJs’ playlists were similar but they had very different approaches to DJing. Hardy’s style was frantic and intense: he played harder, faster, and weirder than anyone else, sometimes running his reel-to-reel backwards, using extreme EQ cuts and boosts, playing his records at the maximum tempo of +8. In contrast, Knuckles’s sets were more structured and organised, his tempos were slower, his mixing style more measured, his performances more sophisticated: Knuckles was keeping disco alive, Hardy was propelling it into an alternative reality. The influence of these two DJs ran through the early development of house music in Chicago, and their selections, mixing and re-editing techniques provided a set of musical references and practices for young aspiring producers. These techniques and DJing experiments — and the many efforts to copy them by other DJs and producers — were the roots of the house music aesthetic, its style, tropes, and defining musical features.

The first early proto-house tracks were often little more than raw audio sketches, made from drum machine beats and sound effects and circulated on 1/4 inch tape reel-to-reel or cassette. Fledging Chicago producer/DJs began making their own re-edits of old tunes, replaying old disco basslines, looping Italian disco drum intros and splicing it all together. These old First Choice, ESG, Isaac Hayes and Loleatta Holloway records were chopped, looped or rebuilt, the parts replayed entirely on cheap synths, the character of the new genre emerging via relatively affordable home studio recording gear. In her Adventures in Wonderland, writer Sheryl Garratt observed that “…when drum and bass patterns once played by skilled musicians were copied on cheap synths that sounded little like the real instrument, they didn’t seem old or stolen. Stripped of their songs, these recycled riffs sounded alien and new, like raw, minimal messages transmitted from another world.”

Chicago House was a genre that coalesced on the dancefloor, created from a culture that had been deemed inferior or passe by the mainstream, like the classic Philadelphia International sound, faceless Italo-Disco or manufactured Euro-synthpop. The music embraced and celebrated the elements of disco that most irked the racists and homophobes: its queerness, its relentless repetition, the synthetic production aesthetic, its narcotic hedonism, egalitarian spirit, its celebration of powerful vocal divas. Then it intensified those aspects further, distilling the genre down into a new, purified version of itself: house music.

It was only a matter of time before these proto-house DJ experiments would progress onto vinyl, and Jesse Saunders’ On and On was the first of several contenders to make it onto vinyl. Its success showed the rest of the city they could also make house music, and the ’85-’87 era saw the release of the original Chicago House canon, largely on two Chicago labels, DJ International and Trax Records. Knuckles and Hardy’s influence could be discerned in the emergence of two Chicago House styles that broadly corresponded to their DJing styles: songs and tracks. Songs were house music that continued in the orthodox R’n’B tradition of vocalists performing verses and choruses, while tracks were abstract, non-vocal releases that lacked traditional song structures and were based around repetitive drum loops, replayed disco basslines and programmed synth parts. While songs were all about the melody, vocal performance and lyrics, tracks focused on repetition, rhythmic complexity, and the sonic pleasures delivered by the otherworldly textures and timbres of synthetic programming. One of the logical conclusions of the popularity of ‘tracks’ was Acid Tracks by Phuture, twelve minutes of a Roland 303 bass synthesiser arpeggio being morphed and twisted in real time over a thudding kick drum. DJ Pierre, Earl ‘Spanky’ Smith and Herbert Jackson’s record was purely about texture and surface sheen, completely abandoning not only traditional song structure but any ‘human’ element at all, and kickstarted an entirely new sub-genre — acid house — that remains popular today.

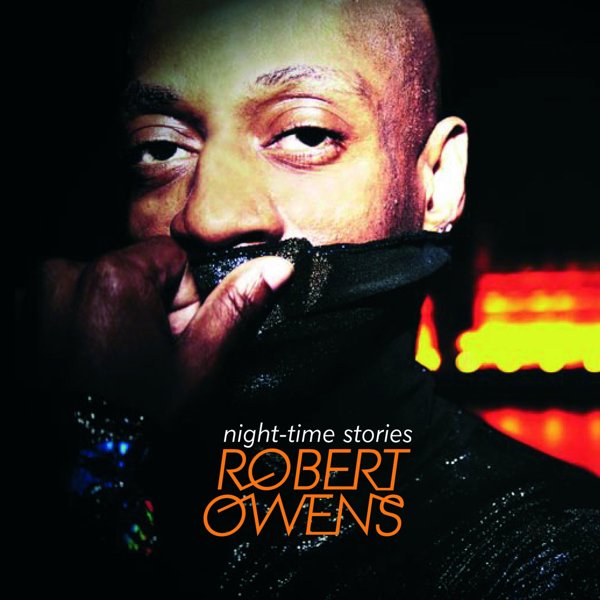

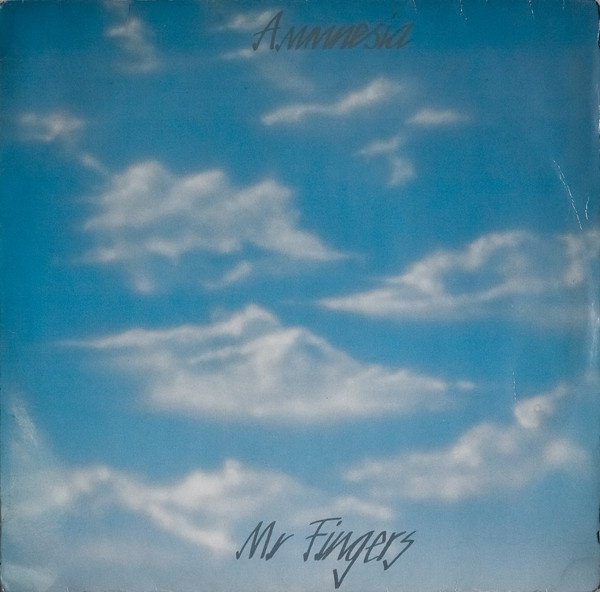

It was a period of international success for many Chicago DJs and artists, and the next step of house music’s journey to global domination was huge international hits from the likes of Lil Louis, Marshall Jefferson, Farley Jackmaster Funk, Steve Hurley, Larry Heard, Joe Smooth and Robert Owens. There’s a perception that after that initial late 80s high point, house music in Chicago experienced a creative lull, and while it’s true that Chicago stopped producing literal world-changing records every month, innovation didn’t just cease. In 1989, Mr. Fingers’ Amnesia album took another step in the maturing and expanding of house music, introducing kosmische, new age and jazz fusion elements. Ron Trent released his seminal 12” Altered States on Armando’s Warehouse records in 1990, while Lil Louis’ ’92 Journey With The Lonely album deftly incorporated jazz into house in its brass lead riffs, classy chords and the skip and shuffle of his basslines.

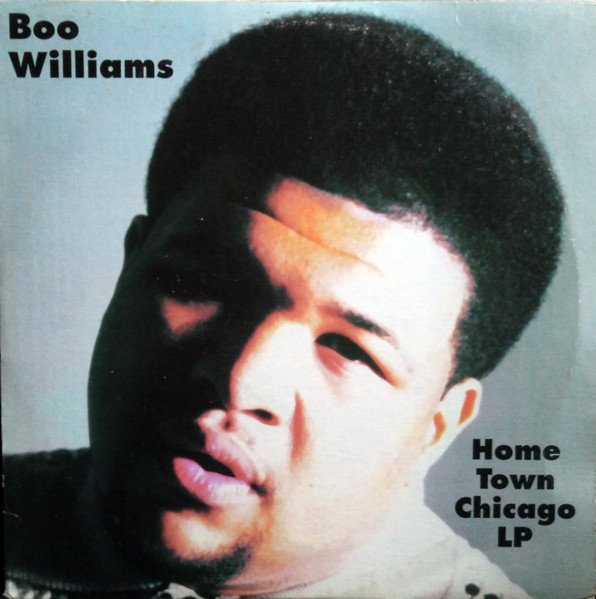

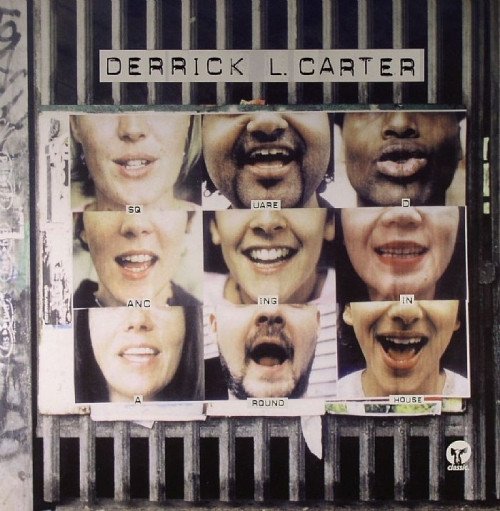

However, there’s no doubt that in the early ’90s, as many of Chicago House’s first generation headlined overseas or remixed pop records, a new ‘second wave’ began to rejuvenate the genre, further reworking and developing the raw musical materials of disco into new shapes and forms. Central to the second wave was Curtis Jones’ (AKA Green Velvet and Cajmere) Cajul and Relief labels, launched in ’92 and ’93, which provided a platform for artists like Glenn Underground, DJ Sneak, Paul Johnson, Boo Williams, Gemini and Derrick Carter. Jones pioneered his own futuristic, leftfield take on the house template, beginning with ’92’s hugely influential twisted proto-tech house “The Perculator,” a sub-bass-laden, squelching, burbling head-turner of a track. Producers like Sneak and Paul Johnson referenced house’s disco roots and Chicago’s love of ‘tracks’ with releases made from relentlessly looped disco samples put through studio filters and effects. Derrick Carter built irresistible funky audio collages that were part-mutated disco, part space-age house, and went on to co-run The Classic Music Company, home to Chi-house classics like Gemini’s “In My Head” and Sneak’s “You Can’t Hide From Your Bud.” Ron Trent and Chez Damier’s Prescription label was launched in ’93, setting new standards of complexity and musicality for Chicago deep house and creating a much-treasured catalogue of shimmering, potent deep house, while Gemini (Spencer Kinsey) co-launched the Guidance label in ’96, building a groundbreaking house catalogue which stretched the definitions of the genre. Felix Da Housecat chose yet another direction, pursuing a tough, techno and electro-flavoured approach, launching the Clashbackk label in ’96, later blending his brand of raw house and techno with electroclash as the decade ended. The turn of the century also saw the appearance of DJ Heather’s excellent Black Cherry label, home to some of the cleanest, freshest house music of the early 2000s.

That there are only male artists in this album selection obscures the central role played by women — vocalists like Taana Gardner, Lady Alma, Barbara Tucker, Liz Torres, Shanna Jackson (Paris Grey), trail-blazing DJs like Lori Branch, Celeste Alexander and the Superjane collective of DJs Heather, Colette, Lady D and Dayhota, promoter Toni Shelton, and countless other female and trans artists, studio staff, songwriters, pluggers, and managers — in the birth and evolution of Chicago House. They may not have recorded albums but their contribution, while as yet largely unwritten, was vital.

That house music took over the world so thoroughly since its Chicago birth is living proof of the power of the genre, and of the creativity and excellence of its originators and practitioners. For many, house is simply the best soundtrack for a party or festival, for some it’s the subject of a lifelong love affair, while for many Chicagoans, house music is not so much a genre as a living culture and potent social force, existing in the context of larger movements like civil rights, black power and Stonewall. No doubt house music has become many things to many people, but one certainty is that its global ubiquity has to be the single biggest, most comprehensive comeback in popular music history: disco really did get its glorious, beautiful revenge.

(Pre-emptive sidenote: this selection of Chicago House albums is made up of personal favourites, and isn’t intended to be a definitive list!)