Free jazz seems like a music designed to be performed by small groups. And indeed, it frequently provides a home for even smaller ensembles than those found in more mainstream forms of jazz. Ornette Coleman’s 1959-61 quartet struck a blow by omitting a piano, while Cecil Taylor limited himself to piano, saxophone (played by Jimmy Lyons) and drums (first Sunny Murray, then Andrew Cyrille) for years. Anthony Braxton’s first quartet consisted of himself, trumpeter Wadada Leo Smith, violinist Leroy Jenkins, and drummer Steve McCall. Peter Brötzmann famously led a bassless trio with pianist Fred Van Hove and drummer Han Bennink, too. There have been countless duo albums, and even solo releases, in the annals of free jazz. But the opposite is also true. There is also a long history of large — sometimes very large — ensemble works within the free/out idiom.

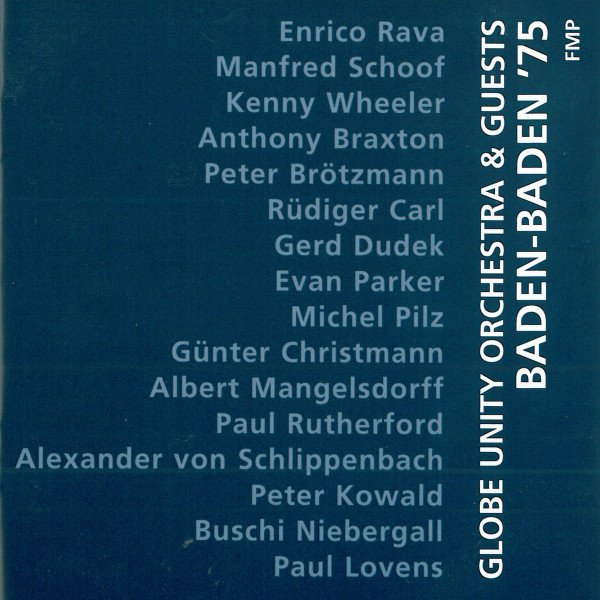

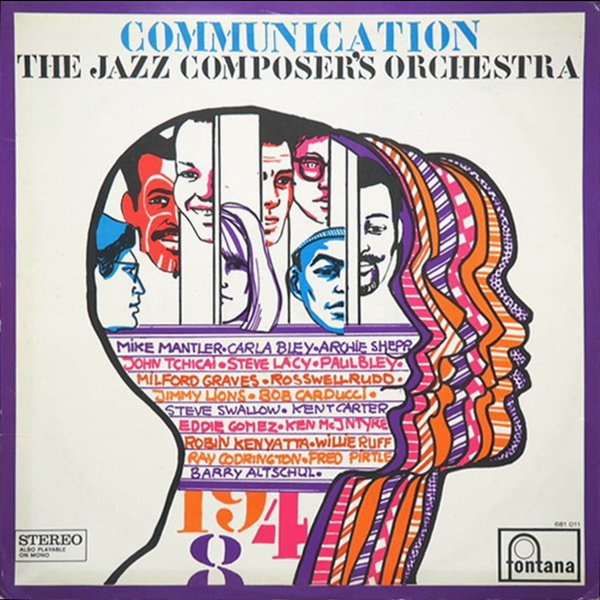

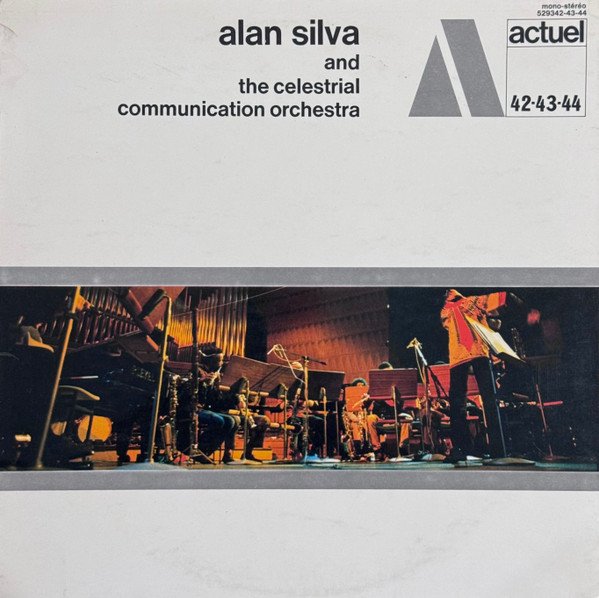

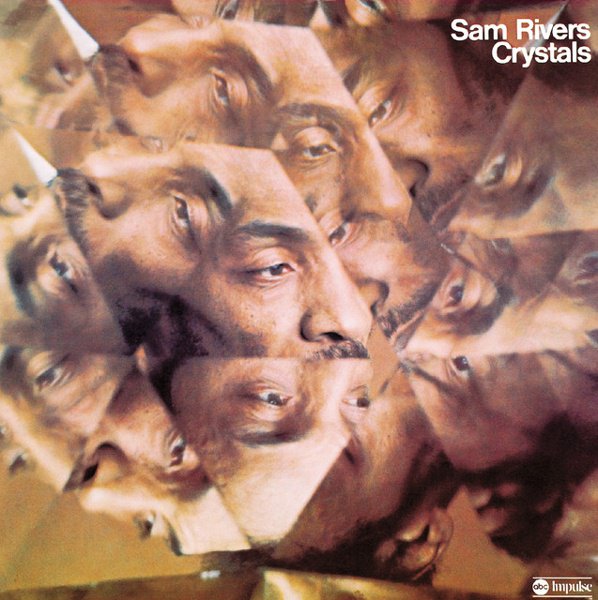

The seeming contradiction of the “free jazz orchestra” is what gives its music such power. How can one ask eighteen or twenty musicians, each committed to the principle of unfettered, highly individualistic improvisation, to work together with the discipline necessary to create something coherent? These works are often written out (though there’s plenty of solo space allotted), but still kept loose enough that a kind of mosaic-like group identity emerges. And when it works, free jazz orchestra music can be a kind of magic trick.

The discipline of big band jazz is essential to its power. Whether it’s the lushness of Duke Ellington’s classic 1950s recordings, the dance-commanding pulse of Count Basie’s 1930s bands, the high energy and modernism of Woody Herman’s 1940s Herd, or any other swinging group of the mid-20th century, when the form was at its peak, traditional big band jazz is about moving as one. The solos are nice, but the charts are the thing.

Free jazz, meanwhile, is about breaking those fetters. Pulse drumming instead of a hard, swinging beat; lengthy solos instead of punchy melodies; ragged arrangements instead of tightly rehearsed charts. Make no mistake, free jazz can offer strong melodies (Ornette Coleman had an instantly recognizable style and an undeniable talent for hooks, and John Coltrane, Anthony Braxton, Pharoah Sanders and Albert Ayler all had memorable tunes), but the focus is often on a single player expressing themselves rather than a group marching forward in lockstep.

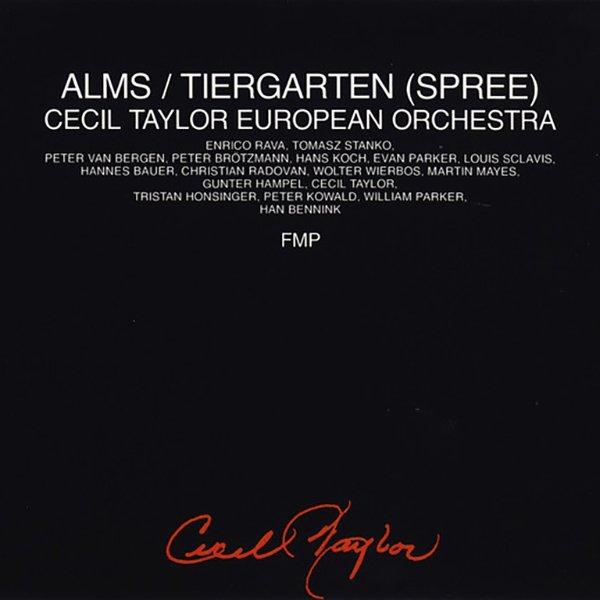

That said, even the most iconoclastic and singular voices in the jazz avant-garde seemed to relish the opportunity to paint on a broad canvas. Cecil Taylor’s large ensemble work is some of his most exciting music, and late in life he convened a big band for an annual NYC residency that spanned close to a decade, though none of the recordings have ever been released.

The albums discussed here are some of the most unique and powerful in all of free jazz, precisely because they succeed in bridging the gap between unfettered improvisation and the sweeping power of an orchestra in full flight.

(Note: We’re leaving the Sun Ra Arkestra out of this discussion, because Sun Ra is a separate subject, always.)