The Hammond Organ Company, led by Laurens Hammond and John M. Hanert, produced its first electric organs in 1935. They were frequently bought by churches that lacked the space or the budget for a pipe organ. The instrument, usually paired with a rotating Leslie speaker, could get quite loud and even offer certain types of vivid sonic extras, including vibrato and chorus effects. The B-3, introduced in 1954, added a “harmonic percussion” effect, allowing the organist to emulate a xylophone or marimba.

Although some jazz performers, like Fats Waller and Count Basie, were using organs as early as the 1920s and 1930s, the instrument was mostly considered a novelty at the time. (Hey, so was the tenor saxophone when it was first introduced.) It wasn’t until the late 1940s and early 1950s that it began to really take off in jazz. Wild Bill Davis, formerly the pianist with Louis Jordan’s Tympany Five, switched to the organ and formed his own very popular trio. But it was the next major organist to come along who would become the face of the instrument for decades.

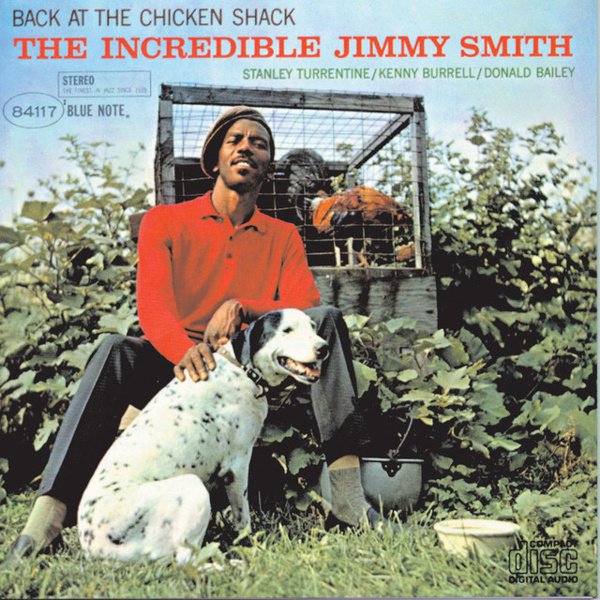

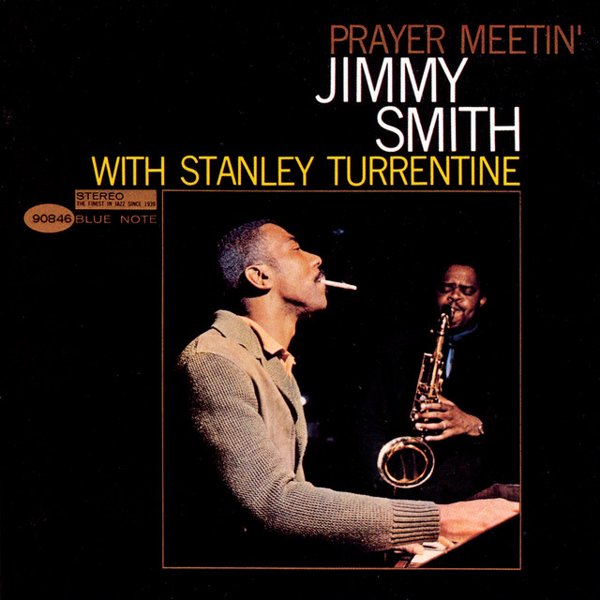

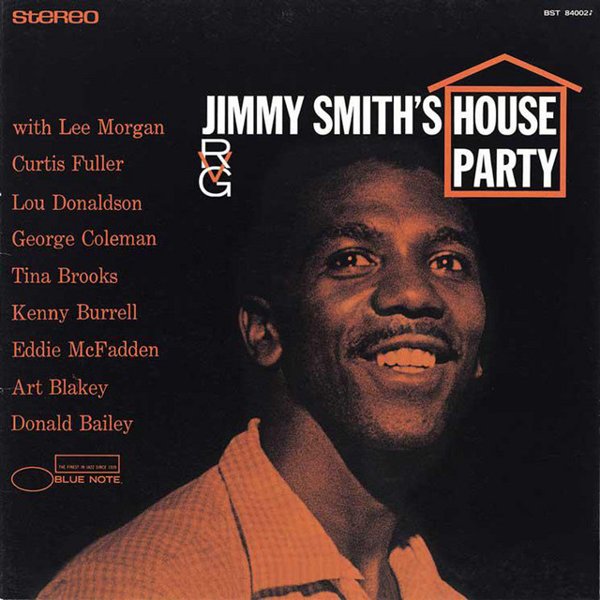

Jimmy Smith, signed to Blue Note Records after a performance in a Philadelphia club, was a virtuoso organist who also laid down absolutely stomping grooves. His debut album, the aptly titled A New Sound… A New Star… Vol. 1, was released in 1956 and was an immediate sensation. His ability to combine pop standards with new hard bop compositions and even splashes of classical music (the album ended with a radical version of Johann Sebastian Bach’s “Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring” retitled “Joy”), all performed with breathtaking technique, revolutionized organ playing.

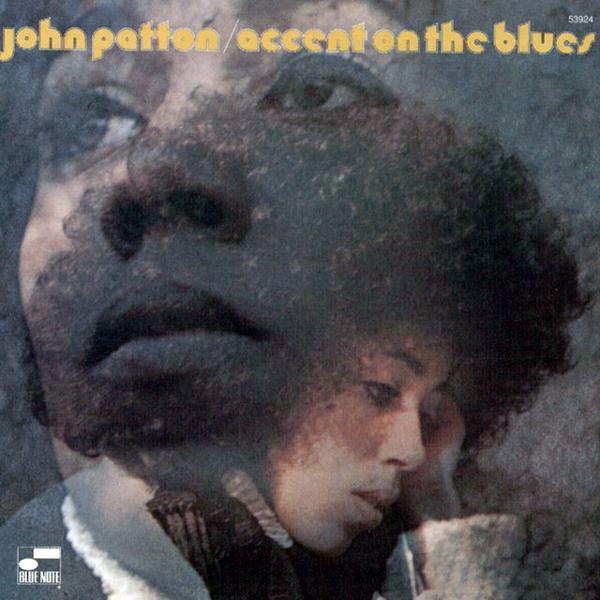

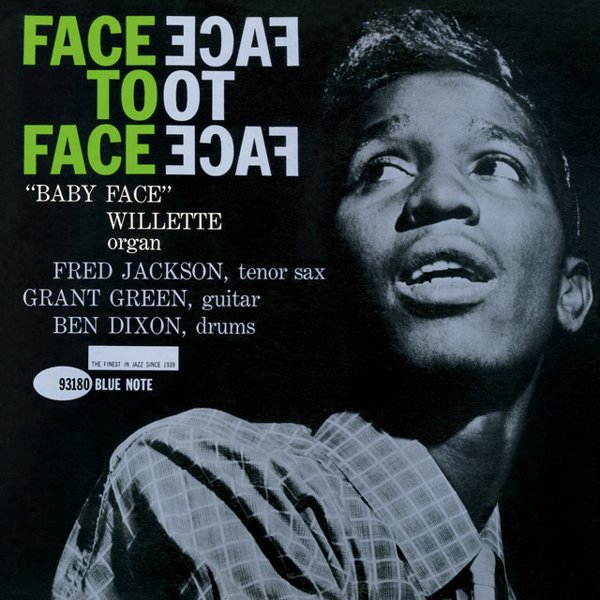

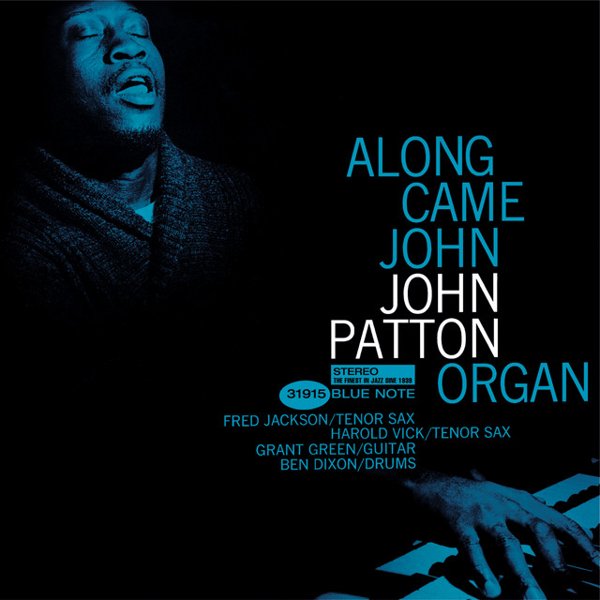

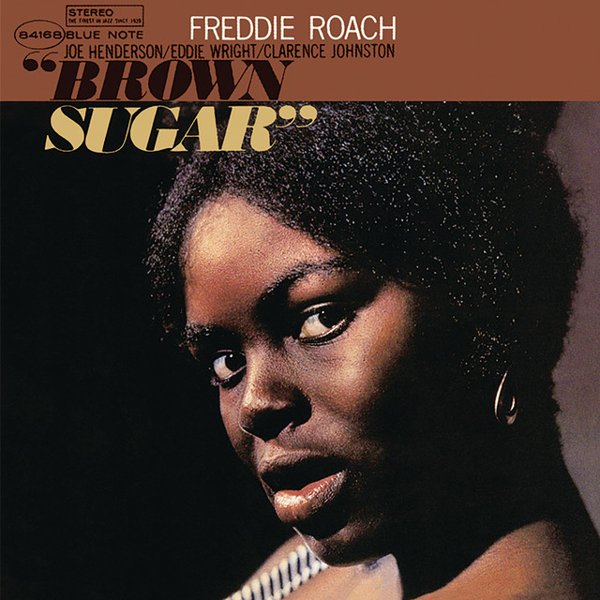

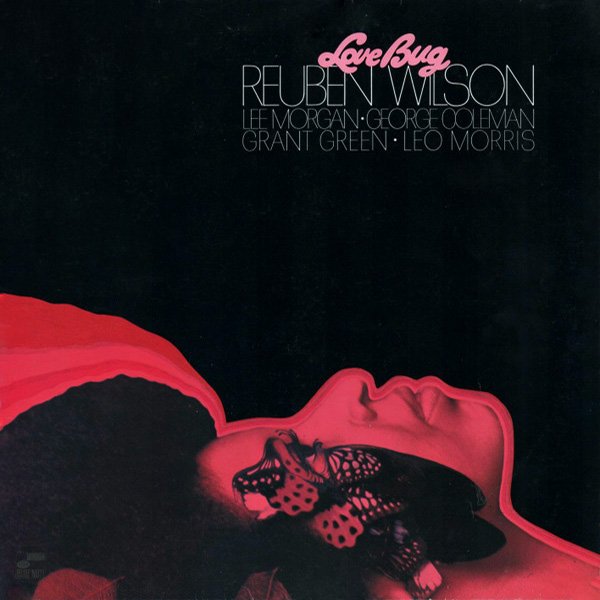

From the late 1950s to the end of the ’60s, groups featuring organ, drums, and either electric guitar or tenor saxophone were among the most popular in jazz. Clubs in black neighborhoods could always pack the house with an organ trio, and artists like Smith, Jimmy McGriff, “Brother” Jack McDuff, Richard “Groove” Holmes, Big John Patton and others played funky, soulful, hard-jamming music that also made the careers of guitarists like Kenny Burrell, Grant Green and George Benson. The album and track titles began to reflect an overtly black, working-class cultural experience, with references to chicken and ribs and, perhaps more importantly, black models on the album covers. In most urban neighborhoods, the organ groups were even more strongly identified with black culture than the free jazz fire-breathers who promoted militant politics on their album sleeves.

Organ jazz was a big part of the music that black audiences often preferred to listen to, along with the Ramsey Lewis Trio; Cannonball Adderley’s funky jams; or Horace Silver’s melodic, finger-snapping tunes. It was never the kind of jazz described as “America’s classical music.” But it sold, not just as albums but as singles that people played on jukeboxes and on the radio. In the 2024 book In With The In Crowd: Popular Jazz In 1960s Black America, author Mike Smith recasts the common narrative of what jazz was “important” while also revealing what an important role jazz played in black life at the time.

He describes an entire social ecosystem, including nightclubs in black neighborhoods, radio stations and the DJs who developed deep relationships with their audiences, and the aforementioned album covers, which began to feature black models, including models with natural hairstyles, for the first time in the mid ’60s.

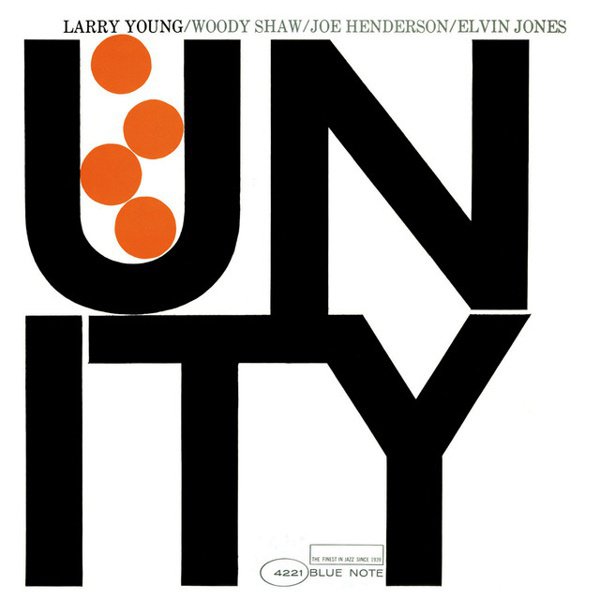

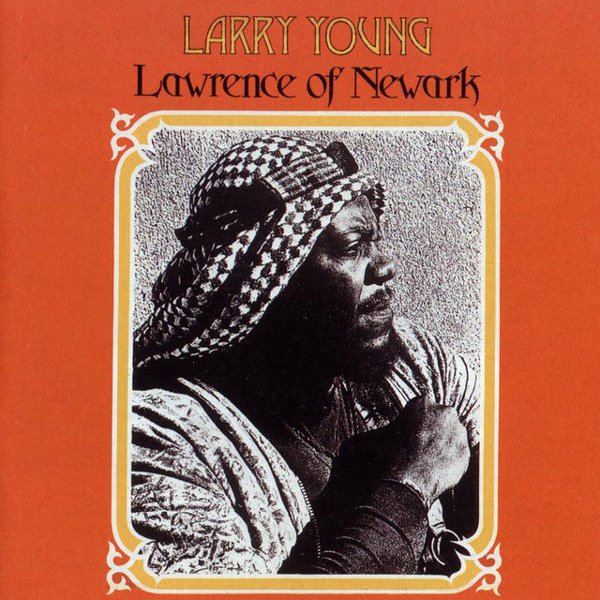

As the Sixties wore on, though, some organ players began to rebel against the grits ’n’ gravy clichés of soul jazz and move in a more adventurous direction. The most exploratory player was Larry Young, whose Blue Note albums were plenty wild, but whose masterpiece, Lawrence of Newark, was a psychedelic space odyssey. Turban-clad Lonnie Smith (who later declared himself a doctor) and Lonnie Liston Smith also took the music out, with Liston working with both Pharoah Sanders and Miles Davis.

Once fusion took over, organ jazz lost its status as the people’s jazz and began to seem like the sound of yesterday. There are still organ groups around, and probably always will be, but now they’re deliberately retro acts. The unique sound of the Hammond B-3 can be emulated with software and a keyboard plugged into one’s laptop, but that doesn’t make the classic organ albums any less stunning.

With just one or two exceptions, every album below was recorded between the late 1950s and the late 1960s, the golden years of organ jazz. And while they may seem superficially similar, the more you listen, the more variations you’ll hear. There are a million ways to play the blues, after all, and the organ proved to be a shockingly versatile instrument in the hands of the masters discussed here.