It’s easy to forget today that the term “baroque” was originally intended as an insult to the musical style that emerged in Western Europe around the turn of the 17th century. The word literally means “overly fancy,” and its original use reflects the conventional wisdom of the European musical establishment at that time: coming out of the Renaissance period, when art music was mostly somber church music and mostly vocal, the efflorescence of virtuosic, highly ornamented, and increasingly secular music during the 17th century seemed to many like an abandonment of cherished norms and values in favor of outlandish and decadent virtuosity.

From the 12th to the 16th centuries, the music produced by trained composers had been written for performance not in concert halls but in chapels and cathedrals, during church services. But secular music, in such forms as dance tunes, troubadour songs, and madrigals, became increasingly prominent as the Renaissance period unfolded, and by the end of the 1500s the stage had been set for a major stylistic shift.

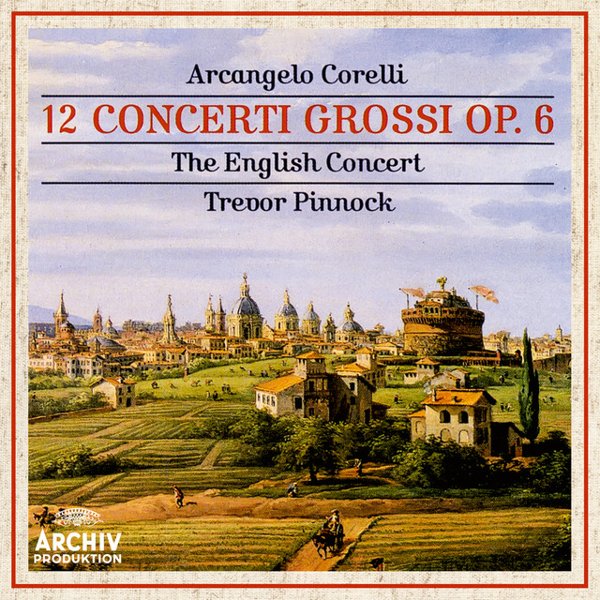

Both vocal and instrumental music took on new and more elaborate forms as the baroque style began to emerge. The modern concerto – an orchestral form characterized by specific structural elements including a prominent solo instrument or (in the case of the concerto grosso) small group of soloists – the opera, the oratorio, and the sonata (with its distinctive organization of themes and movements) all came into full flower during the 17th century, and these forms continued to dominate art music well into the 20th century. During the baroque period the idea of “musical rhetoric” (applications of principles from classical oratory to compositional technique) was explored and applied in a variety of ways, and secular music both vocal and instrumental came to have equal prominence with sacred music – and eventually to dominate the European musical scene. Virtuoso instrumental soloists and vocalists became popular stars, touring the continent and performing to large audiences while commanding significant fees.

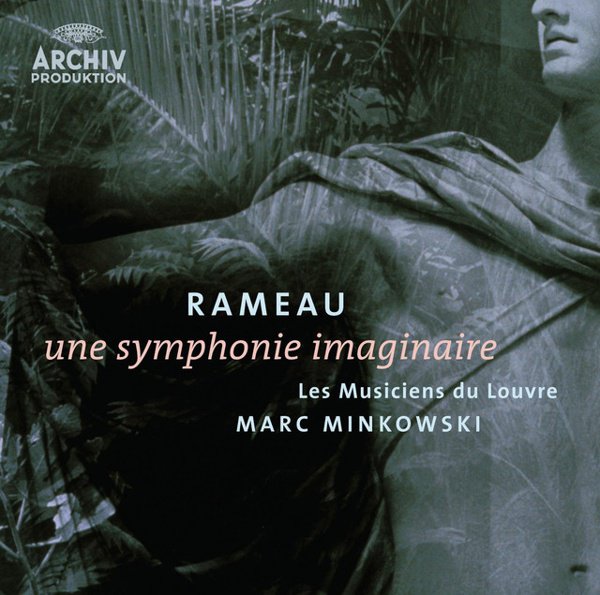

The baroque period was also characterized by competition between different styles of writing and performing: the French galant style was wildly popular during the early- to mid-18th century, but was itself derived from the more dramatic and emotional Italian style, while in Germany a more structurally rigorous approach was dominant, as reflected especially in the music of that country’s towering figure of the period, Johann Sebastian Bach. Bach’s development of counterpoint and fugue remain breathtaking musical accomplishments 300 years later, and his sacred oratorios, Masses, motets and cantatas are monuments of Western music that are still performed and recorded regularly.

Many of the composers whose names are most broadly known today, even by people who would not necessarily consider themselves classical music aficionados, were figures of the baroque period. Bach, Antonio Vivaldi, Johann Pachelbel (author of the D major canon that has become a ubiquitous feature of wedding ceremonies), Georg Friedrich Handel (composer of the Messiah oratorio and the Water Music orchestral suite), Domenico Scarlatti, Marc-Antoine Charpentier, and François Couperin were all baroque composers, and remain household names today. Almost as famous are figures from the transitional period between the Renaissance and baroque, including Claudio Monteverdi and Heinrich Schütz.

Some of the most interesting musical discoveries of the 20th century were of baroque music that was composed outside of Europe, in colonial outposts of Central and South America. When Spanish and Portuguese colonizers occupied areas now known as Mexico, Peru, Brazil, and Argentina, they brought with them Catholic priests, who established missions and cathedrals that needed liturgical music. While some of this music was provided by composers who came over from Europe, they also trained local musicians, which resulted in some magnificent baroque music written in a European style but sometimes incorporating local traditional instruments. This was notably true of the music of Mexican composers Francisco López Capillas and Juan García de Zéspedes, but also of music by European transplants like Gaspar Fernandes and Juan Gutiérrez de Capilla.

Baroque music fell out of fashion during the Romantic period of the 19th century and the modernist era of the early 20th century. But in the 1950s there was in Europe and the United States a resurgence of interest in “early” music (i.e., from the medieval through the early classical periods), and also in the instruments that were used during the medieval, Renaissance, and baroque periods and in the performance practices of those times. Pioneers of what came to be called the early-music movement included the English instrument builder and pedagogue Arnold Dolmetsch, harpsichord exponent Wanda Landowska, singer Alfred Deller, keyboardist/conductor Gustav Leonhardt, and others. Ensembles like New York’s Pro Musica Antiqua, Switzerland’s Schola Cantorum Basiliensis, and the Early Music Consort of London (founded by the brilliant and troubled David Munrow) were formed with the goal of not only bringing to light neglected music of earlier centuries, but also of researching and sharing “historically informed” performance practices on instruments with the physical characteristics of those periods.

The early music movement, with its archaic vocal techniques and sometimes odd-sounding “period instruments,” attracted derision and ridicule from the musical establishment at first, but as musicians became more comfortable with the instruments and their approaches more refined, this movement led to an explosion of interest in music of the baroque period in particular – music by formerly obscure composers and neglected works by established ones soon became standard features of the recording and performing repertoire again. It may be hard to imagine, but Vivaldi’s concerto collection The Four Seasons was hardly ever played in Europe or America during the 19th century; until Pablo Casals recorded them in the 1930s, Bach’s six cello suites – now considered foundational pieces of the cello repertoire – were almost entirely forgotten. While Handel’s Messiah remained persistently popular during the centuries following his death, it’s only in recent years that his many operas have come back to public attention, thanks to the revival of interest in baroque music during the latter decades of the 20th century.

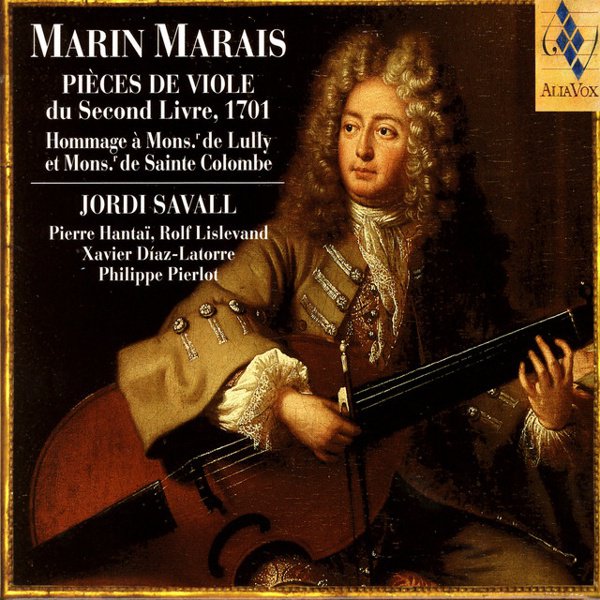

Today, baroque music is a mainstay of concert programs and recording projects, and baroque performance is overwhelmingly dominated by period-instrument ensembles. For the past several decades it has been recordings by ensembles like Tafelmusik, the Academy of Ancient Music, Musica Antiqua Köln, and the English Concert that have set the standard of quality for recordings of baroque music, while long-neglected composers and works continue to be brought to light by dedicated performers and musicologists.